A series of new security challenges tests the EU’s resolve and stability.

By JAMES STAVRIDIS, Politico

The narrow and strategically vital Strait of Gibraltar at the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea is sometimes called “The Pillars of Hercules.” The ancient Greeks believed it to be a by-product of one of Hercules’ mythical labors, which required him to leave the civilized world behind and venture into the chaos and danger of the distant Atlantic. Looking nervously at such a gateway between the known world on one side and an unknown and unstable one on the other is how our European friends must feel today.

Europe’s orderly, sensible, measured security structure — which made a relatively successful transition from the Cold War — is under extreme pressure today. What exists on the other side of the Pillars of Hercules is difficult to make out with any clarity, but the United States needs to help Europe chart the best possible course.

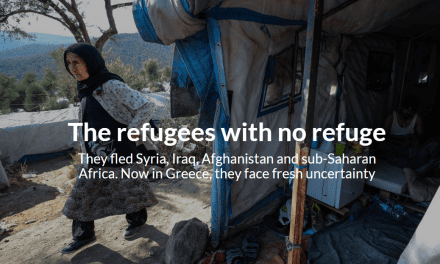

Let’s begin with the challenges: first and foremost, the chaos enveloping the Levant, notably Syria. The outflow of nearly 10 million refugees — over 1 million of which have made their way to Europe — is at the top of the list. Add to that general instability in sub-Saharan Africa, which is creating further migration flows toward Europe. The failure to create any kind of stable post-Gaddafi structure in Libya compounds these challenges, as its vast coastline provides enormous access across what is Europe’s longest “border”: the Mediterranean Sea itself. The number of refugees is predicted to double by next summer, putting more dramatic social strain on Europe and especially on the idea of open borders.

Second, and closely associated with the refugee crisis, is the rise of the Islamic State. A formidable fund-raising organization coupled with exceptionally powerful promotional and recruiting skills, they have unleashed a series of terror attacks across Europe that has deeply unsettled the continent. Their “new model” of completely decentralized terrorist strikes confounds European security skills and undermines confidence in the political model of the European Union. As my good friend General Stanley McChrystal has said, they are “brilliant” and therefore deeply dangerous — especially to Europe, given the geographic proximity and level of radicalized Muslims living in the population already.

Third is the Russian challenge. While no one wants to stumble backwards into another Cold War, Europeans are rattled by events in Ukraine. Despite sanctions and collective efforts to find a diplomatic solution, tension between Russia and the rest of Europe is palpable and will not simply fade away. While Ukraine is probably headed toward becoming yet another “frozen conflict” (like Moldova with Transnistria, and Georgia with South Ossetia and Abkhazia), sporadic attacks, border infringements, and the potential for even higher levels of violence present a challenge to the region.

Turning north, there is growing tension in the Arctic. Of the major Arctic nations and members of the Arctic Council, the majority — Russia, Denmark (Greenland), Norway, Iceland, Sweden, and Finland — is from Europe. The past several years have seen an increasing level of militarization in that delicate and highly strategic region, including new Russian bases and increasing patrols. Climatic conditions alone, never mind the high cost and competing priorities between countries, make it unlikely that there will even be a truly significant military buildup in the High North. Nevertheless, the issue has added to European security concerns.

Fifth, and not often discussed, is Europe’s growing sense of vulnerability to cyber attack. Potential threats run the gamut from major criminal cyber activity (possibly with state acquiesce or even encouragement) to state use of cyber tools to disrupt websites and even electric grids. While attribution is always difficult, the recent downing of a significant portion of the Ukrainian electric grid in December is seen by many as a portent of what’s to come.

And, of course, the economy in Europe continues to struggle, with the Greek situation far from resolved and declining demographics in many parts of the continent.

Europe’s entire security order, while not quite collapsing before our eyes, seems to be increasingly under strain and stress, as though the Pillars of Hercules were swaying as European nations sail into distant and stormy waters without a clear course. This is bad news for the United States, of course, because a strong, confident, and united Europe represents the best pool of available partners for the U.S. in any part of the globe.

What should we do?

From the Western side of the Atlantic, the U.S. must encourage the success of the so-called “European project.” If Europeans lose confidence in NATO, the European Union, the Schengen agreements, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), who and the many other elements that bind them together — loosely, admittedly — all may be lost. The U.S. should encourage Great Britain to stay in the EU; ensure our political leaders articulate the importance of a Europe whole and free, and visit often; send top diplomats and military leaders to posts in Europe; support the European security and political structures in world deliberations like the United Nations, IMF, and World Bank. Obviously, these are decisions that Europeans must make themselves, but encouragement and support from their transatlantic partners can help.

Within Europe, NATO must remain the central pillar of collective security. The inane “competition” between NATO and the European Union should stop, and be replaced by a sensible means of dividing tasks, missions, and skills. This is difficult, frankly, due to the Cyprus situation, which puts Turkey in NATO’s camp and Cyprus in the EU’s, with little love lost between them. But big doors swing on small hinges, and in one small point of light in an otherwise cloudy year, it seems there is growing momentum for a settlement on Cyprus. If that occurs, the changes for better and more sensible cooperation between NATO and the EU in the realm of security is possible.

***

In terms of working Russia, the key will be finding new zones of cooperation, even as Europe confronts Russian adventurism in Ukraine. Some of the elements of cooperation might include political-diplomatic work in Syria; coordination on the refugee crisis, perhaps even a joint flotilla in the Eastern Mediterranean; better counter-narcotic cooperation, especially against the flow of heroin from Afghanistan; working together on counter-terrorism; and considering an expanded counter-piracy mission to the Gulf of Guinea modeled on the successful NATO/EU and Russian cooperation off the Horn of Africa. Challenges in the Arctic are best met through the work of the Arctic Council and convening the military leaders from European member countries each year to create confidence-building measures.

Another important element in shoring up Europe’s security will be in the cyber sphere. While it poses a unique set of barriers to cooperation, the growing threat may catalyze better integration between nations and — more importantly — between the public and private sector. Here the OSCE may be well positioned, as well as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Looking at it as a problem that exists on the nexus of security, commerce, and information — as well as culture and privacy — is key.

Certainly 2016 will be a “year of living dangerously,” as Europe essentially sails beyond the stability of the metaphoric security we took for granted for so long, represented by the Pillars of Hercules. The economic, demographic, and geopolitical pressures on Europe will be immense. And it will require strong leadership, steady strategic communications to a nervous population, help from across the Atlantic, and no small measure of good fortune to keep a secure and united Europe sailing; we should be doing all we can from the United States to help.

Admiral Stavridis was the 16th supreme allied commander at NATO from 2009-2013, and is today the dean of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University.