A meeting between the Patriarchs of Moscow and Constantinople seems to bode well for the country’s aim of autocephaly

By Economist

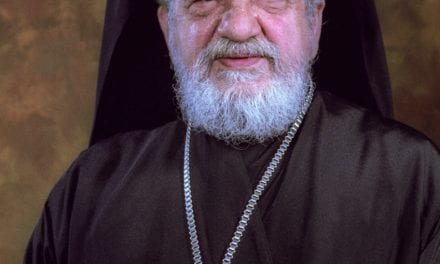

UKRAINIANS who long for a globally recognised national church were left cautiously encouraged by a meeting in Istanbul on August 31st. It took place between two of the most prominent figures in the eastern Christian world: Bartholomew I, the Ecumenical Patriarch, considered “first among equals” in the worldwide Orthodox hierarchy, and Patriarch Kirill of Moscow, to whose spiritual leadership a majority of Russians at least notionally defer.

Ukraine’s president, Petro Poroshenko, has invested huge political capital in his efforts to establish a legitimate national church, promising his people that he will persuade Patriarch Bartholomew to bless the country’s full ecclesiastical independence. The Moscow Patriarchate, which currently controls a majority of Ukraine’s Orthodox parishes, has said that if this wish is granted, it could create the biggest split in Christendom for 1,000 years. The church in Ukraine has largely been controlled from Russia since 1686: the disagreement is in part over whether the transfer of control in 1686 was legitimate and permanent.

The two Patriarchs met for three hours at the headquarters of the Ecumenical Patriarch in Istanbul, who is also styled as the Archbishop of Constantinople and New Rome. There were no common statements afterwards, and the Muscovite visitors did not stay for lunch (this led some observers to conclude that the encounter had been a frosty one). This impression was reinforced when one of the Ecumenical Patriarch’s top advisers, Metropolitan Emmanuel of Paris, said it had already been decided in principle that Ukraine would have an independent church, and there could be no reversal of that decision. All that remained, he added, was to settle certain procedural questions, whose final outcome would be the issuance of a “tomos” or grant of independence.

All this gave heart to independence-minded Ukrainians, including the unrecognised Kiev Patriarchate, which aspires to become the nucleus of a Ukrainian national church. That body is led by an erstwhile hierarch of the Muscovite church, Filaret Denysenko, who proclaimed ecclesiastical independence in 1992 but was denounced as a schismatic, and ultimately excommunicated, by his masters in Moscow. A senior Kievan cleric said the Istanbul meeting, and the apparent disappointment of the Muscovite visitors, boded well for the Ukrainian cause.

The Muscovites made clear afterwards, however, that they have not given up hope of finding a consensual solution to the Ukrainian question. Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, the Oxford-educated cleric who heads the external-affairs arm of the Moscow Patriarchate, had some surprisingly emollient things to say after the Istanbul encounter. He noted that the two Patriarchs (of Constantinople and Moscow) have known and respected each other since the 1970s, and he stressed that for historic reasons, Muscovites hold the Patriarchate of Constantinople in high esteem. He praised as commendably “sober” a promise from the Constantinople camp that they would not resolve one schism (the issue arising from Filaret’s self-separation) by creating yet another schism in the Orthdodox world.

Whatever the differences, the formal respect shown by the Muscovites for their host in Istanbul was striking. Ultra-traditionalists in Russia—and other places, including Greece—sometimes criticise Patriarch Bartholomew for being too open to dialogue and collaboration with the Protestant and Catholic churches. It was noticeable that no such criticism was levelled this time as they passed through the city on the Bosphorus, now the commercial hub of Turkey, and the spiritual source of their faith.

Part of the background to the current standoff over Ukraine is an unusual tension between the wordly authorities of Greece and Russia, which have much in common as historically Orthodox nations. In July, Greece expelled two Russian diplomats and denied entry to two others: one of Greece’s complaints was that Russia was using underhand methods to secure influence over the monastic community of Mount Athos, and over bishops in the surrounding region of northern Greece. Patriarch Bartholomew, like all his recent predecessors, is a member of Turkey’s tiny ethnic-Greek minority. But that does not mean that the Patriarchate of Constantinople will always be perfectly aligned with Athens. It sees its mission as the stewardship of worldwide Orthodoxy, and that involves some tricky balancing acts. Ukraine is proving the most difficult.