By therealnews.com

The former Finance Minister of Greece says that on the night of the July 5th referendum, he realized the pressure had gotten to Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras. Since then, Varoufakis has been campaigning for that “No.”

The YouTube ID of </span>BehqE_-XJm8<span style="font-size: 16px;"> is invalid.

DIMITRI LASCARIS, TRNN: In 2010, hot on the heels of an unprecedented global financial crisis, the Greek government, which was led at the time by Greece’s self-described socialist party PASOK entered into an agreement with the Troika of creditors to borrow hundreds of billions of euros in exchange for its commitment to implement so-called reforms. Those reforms consisted of a broad range of austerity measures that precipitated a sharp decline in the Greek economy, and eventually a full-blown humanitarian crisis.

At the time, one member of the Troika, the IMF, predicted that the economic pain resulting from these measures would be short-lived, and that the measures would ultimately enhance Greece’s ability to service its massive debts. The opposite turned out to be true. Greece’s severe economic contraction ground on, year after year. Since 2010, Greece has experienced a GDP decline that is without precedent for a developed country in peacetime. Nearly 30 percent of Greece’s GDP has been wiped out. The unemployment rate remains at depression-era levels, and Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio, a key measure of its ability to service its debts, has soared ever higher, from a level of approximately 125 percent to 175 percent.

In the cauldron of social upheaval that this crisis precipitated, a new party of the radical left emerged in Greece. That party was called Syriza. In the general election of January, 2015, Syriza almost secured a majority of seats in the Greek parliament and formed power for the first time, with a small right-wing and populist coalition partner called Independent Greeks. I was in Athens for the January 2015 election, and reported for the Real News that the rise of Syriza had engendered a sense of optimism in the Greek people that had not been seen in years. Syriza campaigned on a promise to end the brutal austerity regime of the Troika. Echoing the language of Barack Obama in the 2008 U.S. election, Syriza vowed to give hope to the impoverished Greek people.

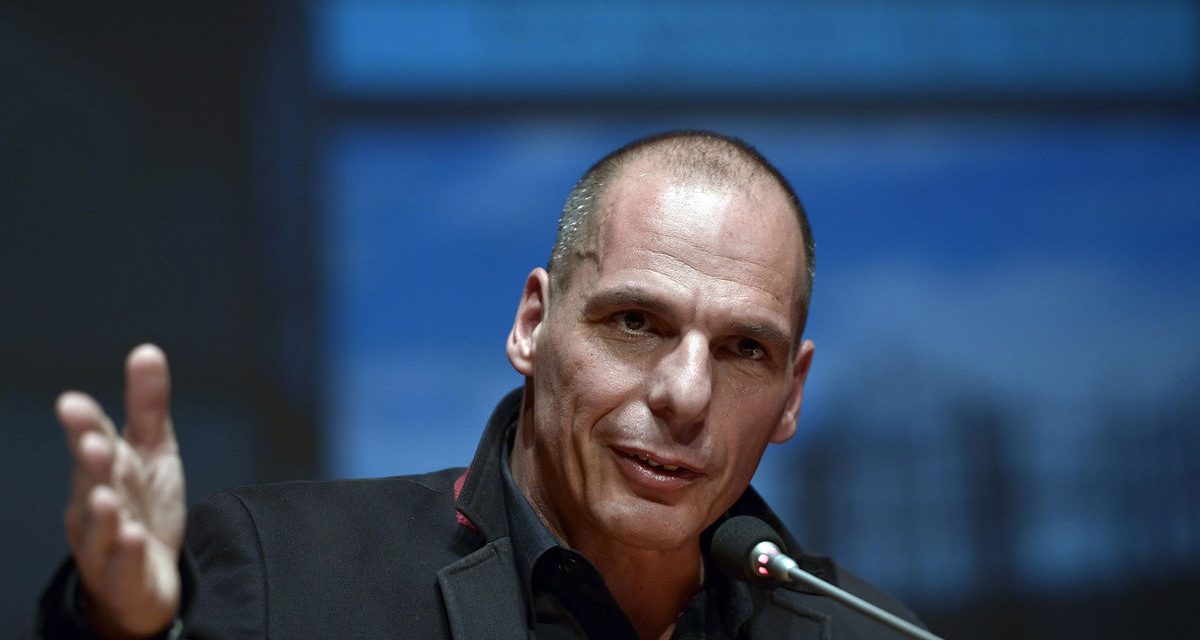

Syriza recruited as its finance minister a man by the name of Yanis Varoufakis. The telegenic Varoufakis had a profile in Greece as an academic economist and a TV pundit, though he had no party political background. Varoufakis’s record left no doubt, however, that he was a fierce opponent of austerity. From the moment that he assumed the post of finance minister of Greece in January 2015, Varoufakis was outspoken in his criticism of the austerity dictates that the Troika had imposed on Greece. He argued tirelessly and with a mountain of evidence to support him that these so-called reforms were undermining Greece’s ability to service its debts, and were fueling the rise of the far right in Greece, and elsewhere in Europe.

As Varoufakis was to learn, however, the priority of the Troika was not to secure a repayment of its loans to Greece, as was widely believed. The true objective of the Troika was to eviscerate the power of organized labor in Greece, as well as the modest social safety net that prior Greek governments had carefully constructed over decades.

Matters came to a head six months following the rise of Syriza to power. In July of 2015, the Greek government held a referendum in which it asked the Greek people to reject the terms of austerity then being demanded by the Troika. In the face of the Troika’s and the Greek oligarchy’s dire warnings of financial Armageddon, and a disorderly expulsion from the eurozone, Greek voters stunned the world by voting overwhelmingly to reject those austerity terms. To the astonishment of the Greek people, however, the Syriza government quickly acceded to a program of austerity that was even worse than the terms of austerity that the Greek electorate had just rejected. Sensing that a humiliating capitulation was in the offing, Yanis Varoufakis resigned as finance minister even as he declared a great victory for the Greek people in the referendum of July 6, 2015.

I had the opportunity to discuss these recent historic developments with Yanis Varoufakis earlier today, and here is what he had to say to the Real News.

Thank you for joining us today, Yanis.

YANIS VAROUFAKIS: Thank you very much, Dimitri. It’s a pleasure to be on the Real News.

LASCARIS: I’d like to begin with that surprising moment when you announced your resignation. And I say it’s surprising because the Greek people had done essentially what you had urged them to do, and they had done so overwhelmingly. Namely, reject the terms that were on the table from the Troika. And at the time you explained that your resignation was motivated by demands of certain partners, as you describe them, of Greece, that you be replaced with someone who was more amenable to them.

Was that the sole reason for your departure at that time? And who were those partners who made that demand?

VAROUFAKIS: Well, they’ve already come out and said who they were. The [persons], the Eurogroup, for instance. But, Dimitri, I was being intentionally economical with the truth on that particular occasion. It was true, what I said, but it wasn’t the whole story. The whole story came out a few weeks later.

During the period, the week of closed banks leading to the referendum, I had stated, for the record, that if the Greek people voted for yes, yes to the austerity package, yes to effectively submitting ourselves once again to the toxic bailout/austerity program, I would resign because I was not elected to Greek parliament and I did not assume the position in the ministry in order to implement what I consider to be an utterly illogical and nonviable package of economic policies.

And the Greek people didn’t vote for yes. They voted as we were directing them to. Overwhelmingly they said no. And extremely courageously, for reasons that I’m sure you know. That night, when I spoke to my prime minister, it became abundantly clear to me that the pressure had gotten to him, and he was going to turn that magnificent no of the Greek populace into a yes. And I was not going to be part of that. So I took my leave. I stole into the night. And since then I’ve been campaigning for that no.

LASCARIS: And I’d like to talk to you a little bit about the effect that that experience had on your thinking about the role of the left in Europe. Before you became the finance minister you authored an op-ed in the Guardian in which you described yourself as an erratic Marxist, and expressed the view that given the realities confronting Europe today, the role of the left should be to stabilize European capitalism rather than to seek to replace it with a socialist system.

In light of the failure of Syriza to implement even a modestly-progressive platform that it campaigned on prior to its first election, do you continue to be of the view that the Left should seek at this stage in the history of Europe simply to stabilize European capitalism rather than to replace it?

VAROUFAKIS: Yes, I’m afraid so, Dimitri. Let me ask a rhetorical question. What if the eurozone were to collapse tomorrow morning, and our different nation-states to return to their national currencies? Which may happen. What will happen is the surplus countries like Germany and the Netherlands, effectively Europe east of the Rhine and north of the Alps, would sink into very deep deflation. The new Deutsch mark that these countries would adopt almost together would skyrocket. Its valued exchange rate would go through the roof. That would dampen immediately exports, and the working poor, the millions of working poor in countries like Germany, would be converted into unemployed poor.

Whereas in the rest of Europe, west of the Rhine and south of the Alps, in the [inaud.] part, plus Greece, we would have a combination of hyperinflation as the new currencies lose their value, and imports go through the roof in terms of their price, while at the same time economic activity, investment, and employment remain extremely low.

And I haven’t–the rhetorical question is now coming. Who’s going to benefit from that? The left? The forces that want to replace capitalism with a more efficient, more productive, more egalitarian system? No. It will be the ultra-right, the ultra-nationalists, the fascists, the Nazis. Marine Le Pen will become president of France. And we would experience once more the 1930s. Remember, in 1929 we had Wall Street imploding. The result very soon after that was the fragmentation of the common currency, the gold standard. And Europe turning in against itself. A very powerful left back then losing the battle to the extreme right. We would have the same thing. It’s not the time to repeat that experience.

LASCARIS: Let’s talk a little bit about the future, what the future holds for Greece in particular. As you know, I’m sure all too painfully, the Syriza government has been implementing a series of so-called reforms at the insistence of the Troika, which many regard as being harsher than the terms previously dictated to the right-wing New Democracy-led government. And recently Alexis Tsipras, the prime minister, expressed the view that 2016 would mark the beginning of the end of the economic crisis in Greece. Do you think that that’s a realistic assessment in light of the nature and harshness of the austerity measures being implemented?

VAROUFAKIS: Dimitri, a simple one-word answer: no. Look. This program that was agreed in August, and which I voted against in Greek parliament, was designed to fail. There is precisely zero probability that it will succeed. The prime minister himself, Tsipras, said so back in August. He described the treaty that he signed, the agreement that he signed on [I think] the 13th of July, as a document that was extracted from him by coup d’etat. These were not my words. These were his.

Now, the great disagreement we had, we had this personally, as well, in a very comradely and friendly way, but it was nevertheless a strong, intellectual disagreement, was this. He said to me, and he said to the parliament, and he said to the public, that we have to accept this toxic, failed program that is never going to work, because if we don’t then the banks will never open again, and we’ll then have blood on the streets, more or less.

Well, what he intended to do was to introduce a parallel program, legislative program, comprising his own, his own government’s agenda for looking after the weak, sustaining those on very low pensions and income. A parallel program, he called it. So there is the [proposed] failed program, which is the price we have to pay according to Prime Minister Tsipras, for the surrender, the defeat. But we introduce a parallel program which justifies why you are staying in power to implement the toxic program.

Now, it is indeed the case that Prime Minister Tsipras and his government tried to do that. In early–late November, early December, they did table in Greek parliament the parallel program. Two days later, the president of the Euro Working Group, which is the effective functionary of the Troika, it came out and said, uh-uh, you have to withdraw that. And a Greek minister humiliated himself and the Greek government by making it sound as if it was his own idea that they should withdraw this parallel program. So this parallel program now has been withdrawn by the Greek government itself, at the behest of the Troika.

So even by the logic of the prime minister, the answer to your question is no.

LASCARIS: And, in, in, in the face of these realities, you yourself have spearheaded and announced recently the creation of a pan-European movement. And could you talk to us a little bit about the nature of that movement, what its goals will be, and how you see the, the, the movement accomplishing those objectives within the realities confronting Europe today?

VAROUFAKIS: Dimitri, the one lesson I learned during those months of negotiations is that [inaud.] less. The common crisis of the whole of the eurozone, which is as common as the Great Depression was common amongst the states of the United States, for all Americans, until and unless this common crisis is dealt with by means of a common approach throughout Europe, that is going to be put together with the result, the consensus, the result, of a conversation amongst progressives across Europe who are determined to do what Franklin Roosevelt did, to create a New Deal for Europe, across borders.

Europe is going to fragment. The eurozone is going to become, even if it succeeds in surviving for a few more years, an [iron cage] for Europeans. And in the end, the only beneficiaries from this process of fragmentation will be the bigots, the racists, the Nazis, the fascists, and all those people who flourish when shared prosperity becomes a forgotten [inaud.].

So the idea is to start something that we’ve never tried before. A movement which is not the result of alliance between movements that have already been set up in member states, but to start a movement afresh, across borders, involving all those of us who saw what happened to, during the Athens Spring, as we called it, as an opportunity to rethink what needs to be done in Europe.

So beginning on the 9th of February in Berlin, and whoever wants to join, it is completely flat management, totally democratic and cooperative movement, is going to be welcomed with open arms. We are not going to allow ourselves to start any sentence with the words ‘the Germans’ or ‘the Greeks’ or ‘the French’, as any such sentence leads to generalizations that divisive. We’re in it together. It’s a Utopian project. It’s probably going to fail. But the alternative is a frightful dystopia.

LASCARIS: I very much hope we’ll have the opportunity to speak to you again in the future.

VAROUFAKIS: Thank you, Dimitri.

LASCARIS: And this is Dimitri Lascaris for the Real News.